How David Beckham’s ‘brand’ was made

David Beckham couldn’t find 10p to feed the electricity meter. It was a snowy December evening in 1994 and he had just stepped through the front door of his house on the outskirts of Manchester with the PR maven Alan Edwards, who he had met earlier that day and invited over for dinner. Edwards supplied the change to get the lights on. “The place wasn’t exactly the Four Seasons, more like something I’d seen in a Hovis ad. It really was what footballers used to call ‘digs’,” remembers Edwards. Beckham, a shy, London-born son of a gas fitter, had only just started his Premier League football career with United. “He struggled with a can opener for some baked beans. That’s how basic this all was.”

Twenty-one years later, Beckham, his wife, Victoria, and their four children, are estimated to be worth £470 million and counting, making the family over £130m wealthier than the Queen. A natural companion for Tony Blair and Lord Coe when the UK bid for the 2012 Olympics, Beckham now moves effortlessly as an ambassador on the global stage. His fame is so pervasive that, as a recent documentary showed, it takes a trip into the depths of the Amazon rainforest to find people who don’t know his face. And all this despite the fact that by the time he celebrated his 40th birthday last May – in the company of Tom Cruise, Guy Ritchie and Liv Tyler – he had retired from football, the career on which his stardom was predicated, to focus on business, specifically fashion. When GQ asked the designer Tommy Hilfiger to define Beckham’s status in the industry, his answer was unequivocal: “He is the men’s fashion icon of today, undoubtedly No1.”

“As a recent documentary showed, it takes a trip into the depths of the Amazon rainforest to find people who don’t know Beckham’s face.”

In a world in which the post-career ambitions of even the most successful footballers rarely stretch beyond punditry, how did Beckham get here? Some clues can be found back on that Manchester night in 1994. As Edwards recalls, “David launched into his vision for the future of football and it was mesmerising. It was one of those unusual moments that you get in a career when you realise you’re sitting in the presence of some sort of greatness.” That evening, Beckham spoke about the women’s game, about America being the next frontier and about standing up against racism and homophobia. He also asked Edwards for advice about a photo shoot. “He was going to do Sunday Times Style and wanted an Elvis look, which for a footballer was unprecedented.” Even at this early stage it was clear Beckham had a drive to do more than merely score goals, and he knew how: by using his image to transcend the game.

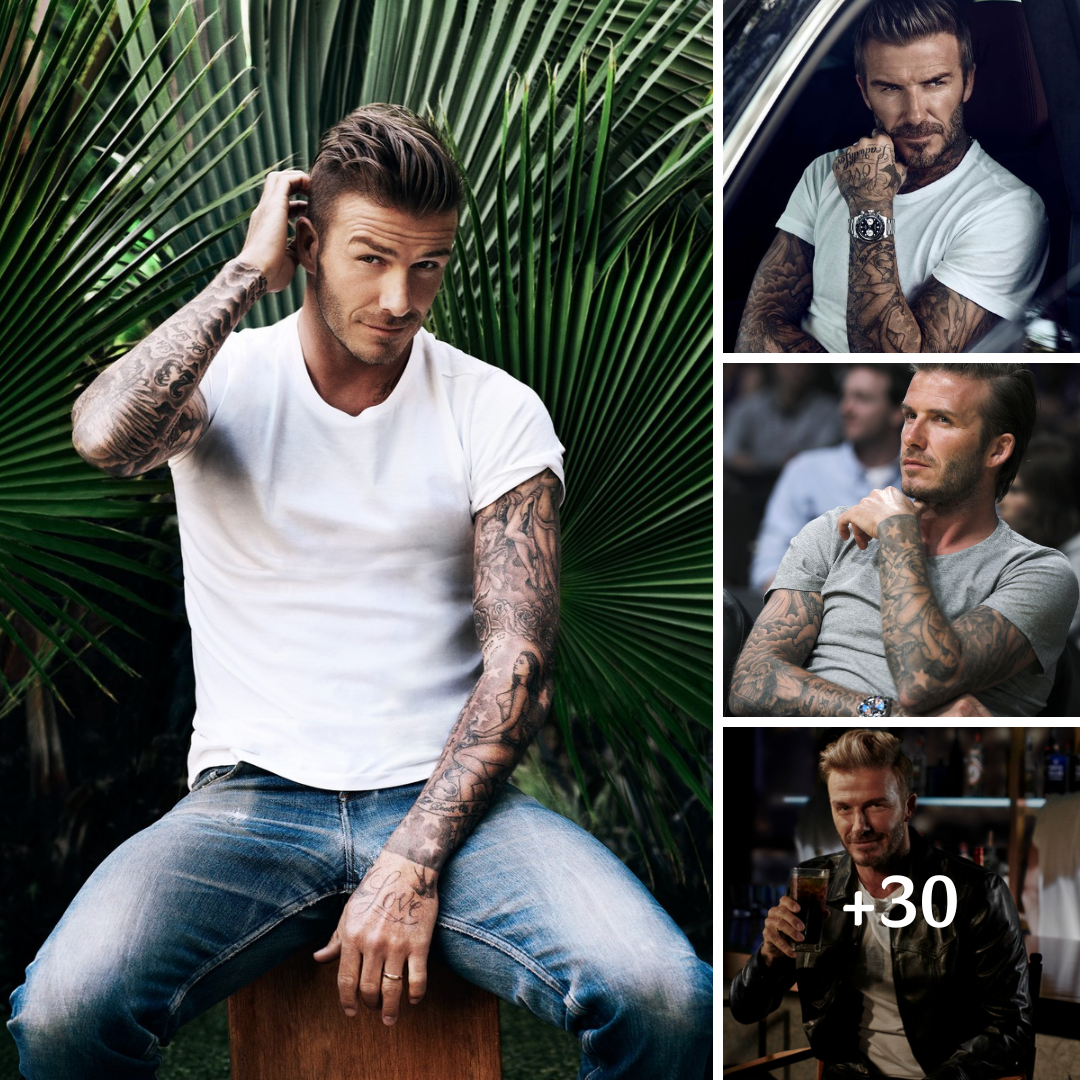

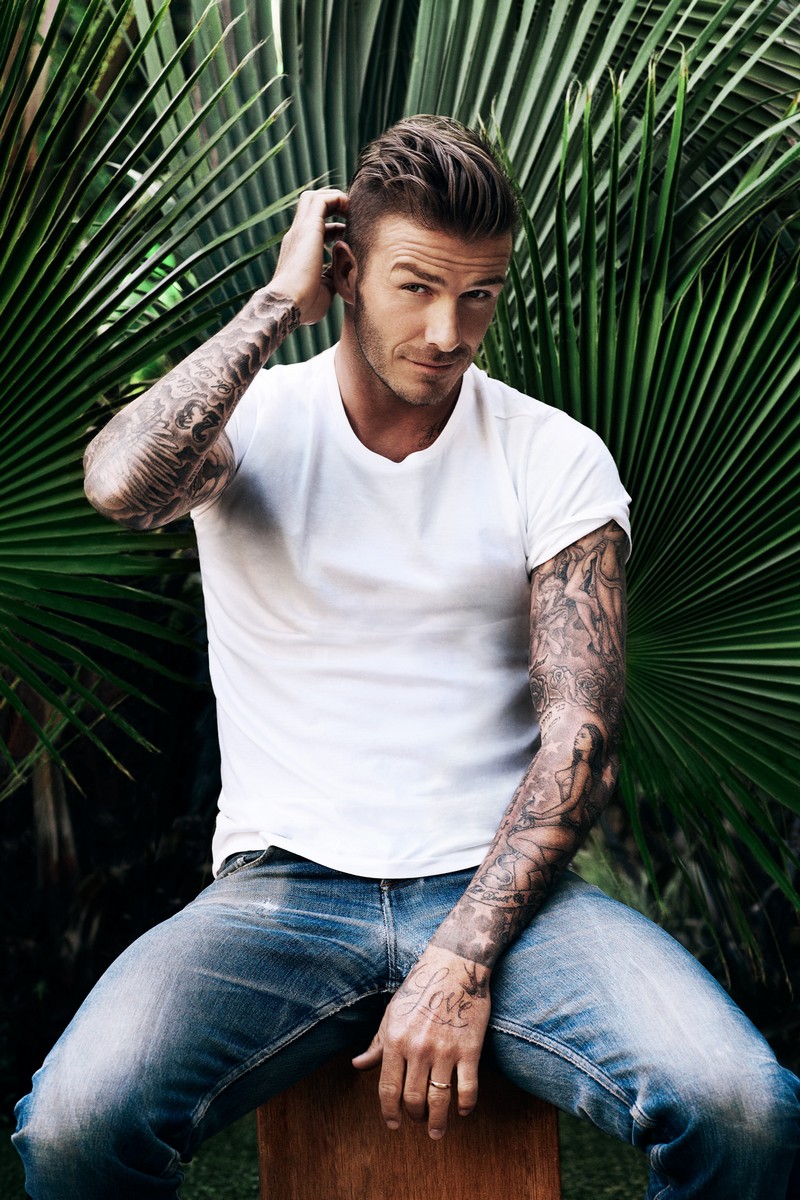

The greatest living photographers have helped forge that image. From Annie Leibovitz to Peter Lindbergh, Inez and Vinoodh to Steven Klein, all have chronicled his changing looks in pictures that arrest, surprise and complicate. Now, for the first time, their work is being brought together for David Beckham: The Man, an exhibition that opened in February at London’s Phillips Galleries. It’s a fundraising effort for 7: The David Beckham Unicef Fund (in collaboration with the photographic charity Positive View Foundation) yet it also has a grander aim: commissioning 50 new works featuring Beckham from names such as Jeff Koons, Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst. When the show is re-exhibited in London next spring, before embarking on a two-year tour across six other countries, these will be displayed alongside the existing photographs. It will mark the next phase in Beckham’s evolution: becoming immortalised in art.

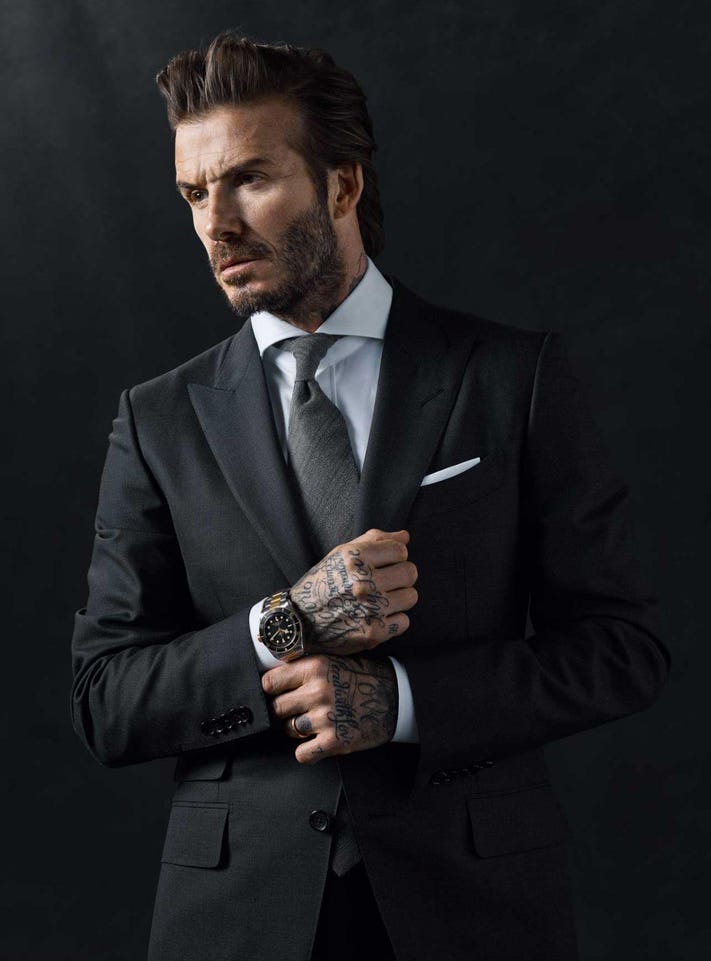

Rewind to a time before Beckham. Football and fashion were not regular bedfellows. George Best might have sported a few Lincroft Kilgour pieces, sure, but that was nothing compared with Beckham’s willingness to wear a sarong or Alice band. Over his footballing career, from Manchester United to Real Madrid, Milan and finally LA Galaxy – and across his changing style, from gender-bending experimentation to more calibrated luxury – Beckham has used fashion to go beyond the sport. Not only in commercial tie-ups with the likes of Armani, Police and Belstaff, but also stylish shoots for glossies such as Vanity Fair and fashion titles including W and 10 – sections of the newsstand where footballers did not usually appear as cover stars.

Beckham has always said that his enthusiasm for fashion is not a cynical concoction. He traces it to the manager of his Sunday league team, who made the players dress up in shirts and ties when travelling to cup matches so that they looked smarter than the opposition. But his interest was amplified by the people around him. Victoria, who he met in 1997 when the Spice Girls juggernaut was at full power, not only magnified his celebrity but nurtured his wardrobe. And his media-savvy decision to hire Edwards, a publicist retained from 1997 to 2003 who specialised in entertainment – in making stars – helped put fashion at the heart of Beckham’s image. “I look at everything on a long-term basis. I work with musicians and it’s always about the next album, the next tour, the bigger brand,” says Edwards. “But often with footballers their agent handles the PR, and then, understandably, the financial question comes first: ‘What’s the gain from doing this shoot?’ To me, that wasn’t the question. You don’t get cash for doing things like the Sunday Times but the value to the brand is incredible. Instead, I would ask, ‘Is this something we couldn’t normally have got into? Does it put David in front of a different audience?’”

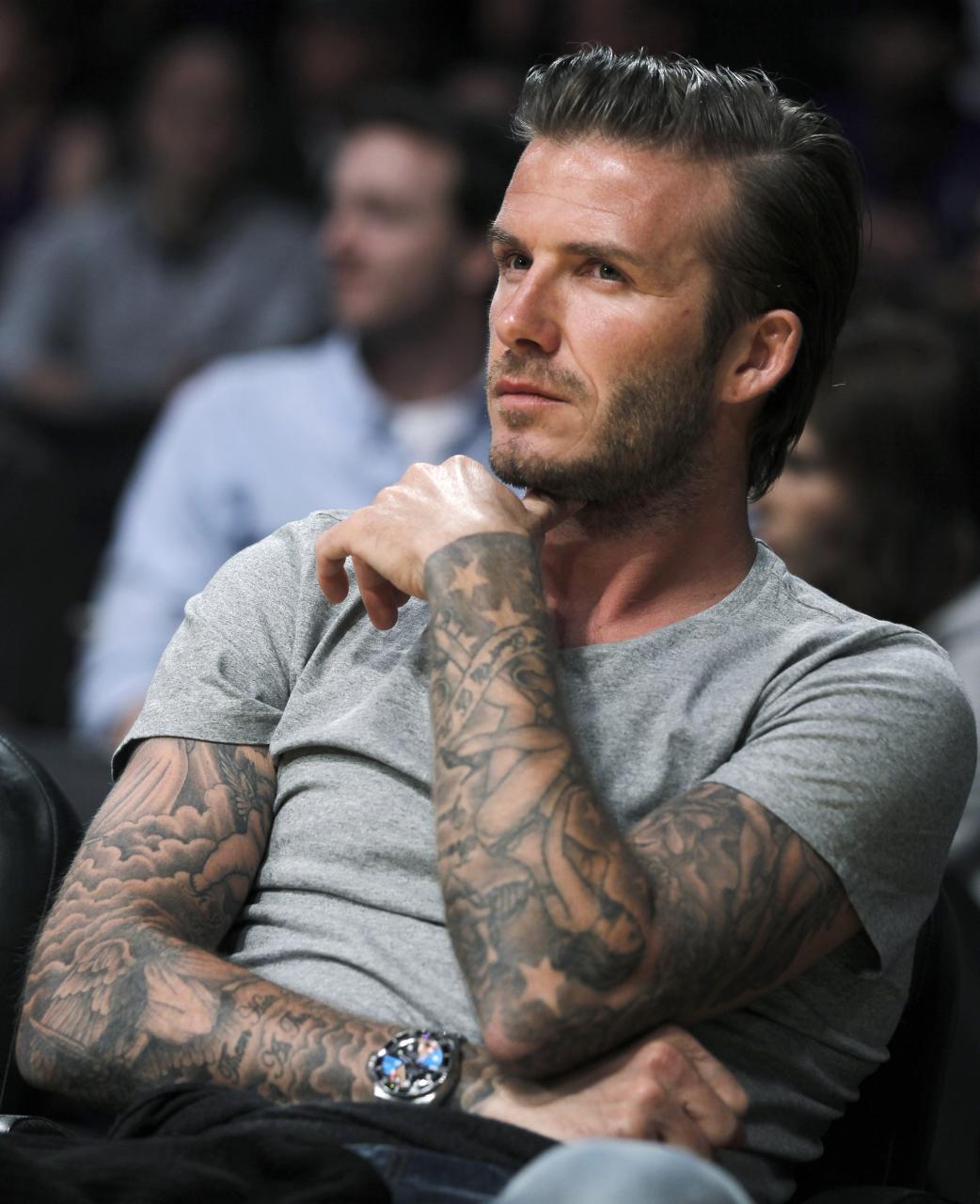

One such audience was the gay market. As the “biggest metrosexual in Britain” – according to Mark Simpson, the journalist who coined the term – Beckham had natural crossover appeal and he played on this in his shoots. In a famous instance, he oiled his chest and had his nails painted for a 2002 David LaChapelle GQ portfolio. Equally, he positioned himself as extremely female-friendly, being the first man to grace the cover of both Marie Claire and Elle. His tattoos, which have crept across most of his upper body, are mainly about his wife and children.

For all Beckham’s devastating crosses and trademark free-kicks – not to mention his record as the only English football player in history to win championships in four countries – Sir Alex Ferguson did not consider him world class. The former Manchester United manager wrote in his 2015 book Leading that he only ever worked with four such players: Eric Cantona, Ryan Giggs, Paul Scholes and Cristiano Ronaldo. But Beckham’s influence developed far beyond that of everyone on the list bar Ronaldo. Beckham didn’t just define hairstyle trends, he helped reshape male culture. As Jamie Redknapp, whose football career spans roughly the same timeframe as Beckham’s, once told GQ, “When I first started at Liverpool, if I’d turned up with a wash bag I’d have been slaughtered by the likes of Ronnie Whelan and Steve McMahon. Now, the boys will ask, ‘Has anyone got any face wash or moisturiser?’ All credit to David Beckham, who made that happen more than anyone.” To Tommy Hilfiger, Beckham “unlocked a door for sports fans to care about fashion. A lot of men who are sports fans are not always so fashionable; David cares about fashion but still looks nonchalant.”

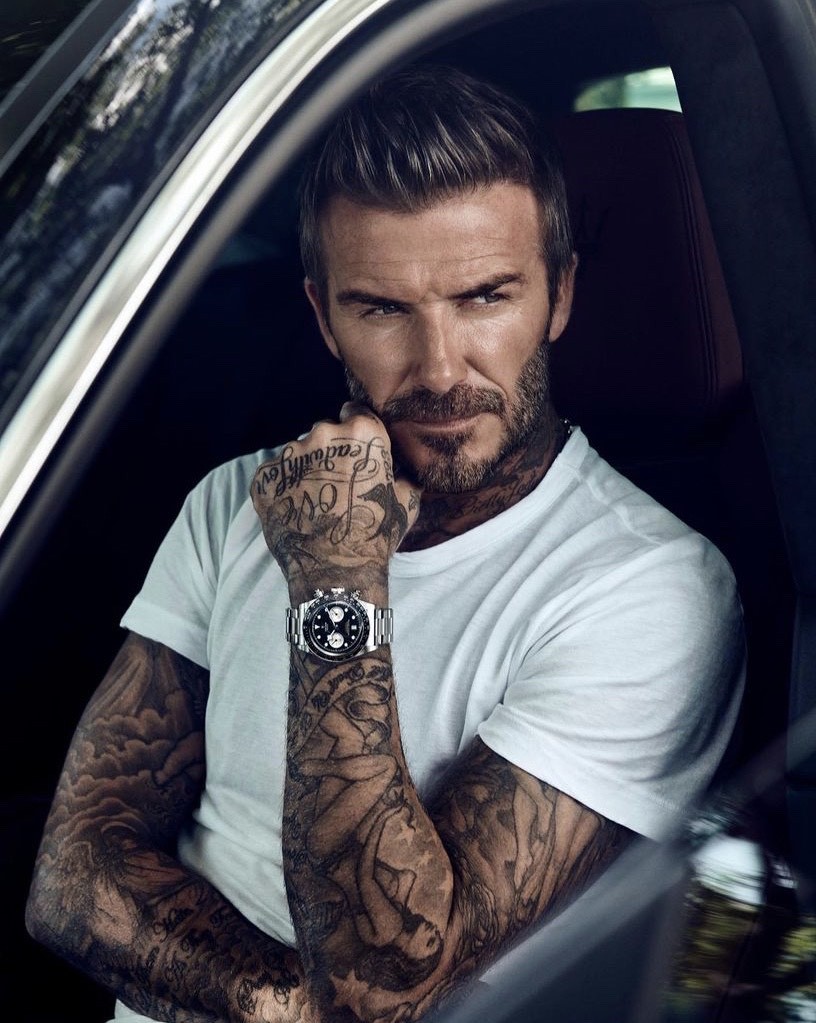

That influence was enhanced by Beckham’s near-silence. His management, XIX Entertainment, are notoriously cautious about his media activity and, as he wrote in his 2000 autobiography Beckham: My World, “I’ve learnt not to say too much in interviews.” This strategy of letting the pictures do the bulk of the talking communicates one thing above all others: simply, his physical form. In Hilfiger’s estimation “women like to look at him, they think he’s sexy and hot, and men, generally, want to look like him” (no wonder that after Beckham renegotiated his Manchester United contract in 2002, he secured an unparalleled £20,000 a week solely in image rights). By dealing in surface, he remains a cipher with which almost anyone can engage, regardless of race, politics or religion.

“He is a triumph of consumer capitalism. In Bangkok, his image actually appears alongside the Buddha at the Wat Pariwas temple.”

Good looks don’t automatically translate into enduring images, so why are Beckham shoots so successful? Ask any of the photographers who have collaborated with him, and they will comment on his work ethic. In the same way that he rose to the top of his game by obsessively practising kick after kick (Ferguson once recalled how Beckham trained “with a relentless application that the vast majority of less gifted players wouldn’t contemplate”), Beckham has also drilled himself, over the past two decades, on how to deliver in front of the lens. The photographer Nadav Kander recalls that, “He was much more interested in how to hold himself than I’ve ever found with a sportsman before.” He is so involved, in fact, that he practically directs his own shoots. When Vincent Peters wanted to photograph him as a soldier, the original concept was more elaborate. “I actually had a Vietnam-style metal helmet for him,” says Peters. “But Beckham said, ‘No, I think that’s pushing in the wrong direction.’ He knew exactly what he wanted.”

The polish of this one-man brand is insanely marketable. In 2014, a year after retirement, Beckham netted £47.9m, more than any former athlete in the world other than Michael Jordan. Steve Martin, chief executive of M&C Saatchi Sport & Entertainment, says that Beckham’s earning power comes from a smart business move. “It’s very simple,” says Martin. “Beckham has evolved from being a sponsored individual to an equity owner. He’s been ahead of the game, which comes from very, very, very good advice from people around him.” In other words, team Beckham has leveraged his image to secure cuts of the businesses with which he is associated. Take his recent venture with British tailor Kent & Curwen; Beckham’s company, Seven Global, will take five per cent of net retail sales and ten per cent of net wholesale sales related to his involvement.

And yet, here’s the thing: he seems so normal. Part of that is down to the tough spells in his career, such as the abuse he suffered following his red card at the 1998 World Cup, which make him relatable. But it’s also a function of tremendous PR. There are his recent documentaries Into The Unknown and For The Love Of The Game, which showcase his warm persona (see, he ribs his friends just like we do!), but his social media activity is perhaps more significant. He posts seemingly unmediated updates about his everyday life that telegraph consistent, family-man values to many millions around the globe. Significantly, his most important channel is fast becoming Instagram.

The Beckham phenomenon is celebrity at its most postmodern. He is a triumph of consumer capitalism, idolised in much the same way as the gods of yore. In Bangkok, his image actually appears alongside the Buddha at the Wat Pariwas temple. So perhaps it’s inevitable that he would become immortalised in art, in the manner of Elvis and Marilyn Monroe before him, whether he commissioned the pieces himself or not. Jeff Koons’ idea? A giant pair of golden balls. Introducing: David Beckham, art icon.

A version of this article originally appeared as the cover story in the March 2016 issue of GQ